On Leaving Nothing Untapped

by Camille Gallogly Bacon

Chicago-based artist zakkiyyah najeebah dumas o’neal’s solo exhibition at Indiana University’s (IU) Gayle Karch Cook Center for Public Arts and Humanities, “This Irrepressible Need to Fulfill Myself In Every Way Possible,” basks in the sense of renewal and possibility that flows in the wake of sincere investments in one’s own becoming. Drawing its title from writer and film maker Kathleen Collins’ seminal publication, “Notes From a Black Woman’s Diary,” the exhibition recalls a lineage of Black feminist foremothers, including Audre Lorde, Lorraine Hansberry, Camille Billops, Jesse Maples and, of course, Collins herself, whose philosophies both animate and serve as impetus for much of dumas o’neal’s own work.

“This Irrepressible Need to Fulfill Myself In Every Way Possible” was born out of dumas o’neal’s time as the inaugural Engaged Artist-In-Residence at IU. Throughout her residency, the artist spent time engaging the university’s Black Film Center archives (which includes an edition of Collins’ film Losing Ground), studying Collins’ text (mentioned above), connecting with Black students at the Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center and contemplating the “intense and fraught matrix of institutional spaces” with Art History faculty member Dr. Faye Gleisser. The artist expressed that her time at IU “further reinforced [her] commitment to a wrenching need to not only find fulfillment in the everyday, but [to] offer it up as a co-thinking space between [herself] and those who view [her] work.”

The exhibition includes seven photographs and a single-channel video-cum-collage, all of which bear a signifier of “entry #” in their titles, thereby maintaining a conceptual link with Collins’ diary entries. All eight works prominently feature landscapes — some rugged and dry, some lush with flora — and seven of them prominently figure the horizon. In sum, this exhibition is a glistening visual and sonic parable that bodes the possibility of retreat, restoration and reprieve: a state-of-being seldom granted to Black women,1 but one we are, nonetheless, learning to imagine and listen for. “This Irrepressible Need to Fulfill Myself In Every Way Possible” is indeed a product of and testament to such imagining and listening.

Upon entering the exhibition space, I first encountered the seven photographic works, all of which were mounted on three traditional white-cube-esque walls. Rather than pause to take them in upon entrance, my curious ear carried me past the photographs and towards the alcove in the back, which exuded an aquatic hum resembling that of the Rossby Whistle. As I approached the alcove, the sound intensified and coursed through my weary nervous system, which was fighting a valiant battle against the attendant winter charms of seasonal depression and bone-chilling Midwestern weather. As I wandered towards the tantalizing hum, I realized I had arrived at the exhibition cold, in all senses of the word, clutching a subconscious need to thaw at the level of the spirit. A chance to feel safe enough to melt a little is what I was listening for, and dumas o’neal’s work delivered in spades.

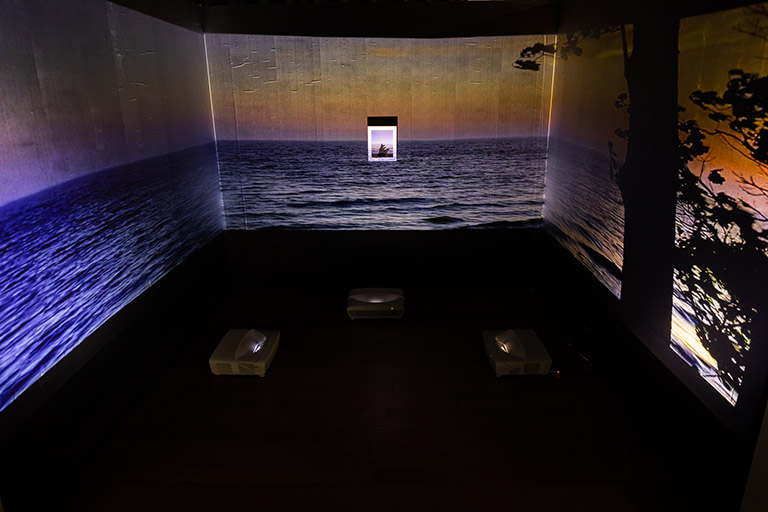

Upon turning the corner, as if the work bent across time to bear witness to and satisfy my silent plee, I was immersed in a chorus of warmth: entry #8 (if I dream it, I can have it), a looped, panoramic video of a sunset blazing over Lake Michigan. Recorded by the artist from an elevated point in the shoreline, the frame captured the silhouette of a tree swaying, unencumbered, in the wind, an incredible volume of water and the sweeping horizon taking shape beyond the shore.

entry #8 (if I dream it, I can have it) was projected across three black, vertical surfaces, each conjoined at 90 degree angles to form a black-box theater of sorts, and also a literal space of retreat from the other half of the exhibition space. The viewing bench was positioned such that I felt I “inside” the scene itself, almost as if I was sitting right beside the artist at the moment she captured the footage, as the vast horizon stretched to swallow me on both sides. As I sat to take in the film, I felt every ghost I arrived with flee and every cell I am composed of settle — as is the quiet, alchemical magic of time spent with dumas o’neal’s work.

The screen in the middle was overlaid by a 8x10” photograph of the artist’s silhouetted hand, as she reached, infinitely, towards the space before her, thereby forming a multi-media collage of sorts. I beheld the photo, static amidst the ceaselessly shifting video and, for a long while, recalled the exhibition’s title as a means of apprehending what was before me. After tossing and twirling the words “this irrepressible need to fulfill myself in every way possible” around in my mouth and mind, what returned to me was an observation of the voracity of Collins’ sentiment. Afterall, she was not only demanding that she be fulfilled, but that said fulfillment arise “in every way possible.” Relatedly, the presence of the artist’s hand reaching towards the horizon revealed a similar voracity, especially when scale is considered: the photograph of dumas o’neal’s hand is miniscule relative to the grandeur of the surfaces onto which the video was projected and yet, its presence is a formidable, persisting one. By no means can dumas o’neal’s hand contain the horizon it tickles, and yet…

To this end, we may consider the enduring wisdom of theorist José Muñoz, who conceptualizes queerness (for which the horizon is a metaphor) as “that thing that lets us feel that this world is not enough.” Similarly, implied by dumas o’neal’s reach towards the horizon is an admission that “this world,” perhaps partially symbolized by the shoreline from which she reaches, is not one built to sustain her, nor those she loves, thereby also nodding to the urgent need to remember and create alternative worlds, as well as sustainable modes of inhabiting them.2 To this end, the artist expresses: “The environments visualized in this body of work are my offering of a sense of elsewhere.” Certainly, the installation strategy in tandem with the vastness of the scene depicted point to the existence of “elsewhere” and the presence of dumas o’neal’s hand within the endless visual plane calls the materialization of “elsewhere” into being.

After soaking in the generous reality beckoned towards in entry #8 (if I dream it, I can have it), I could not shake the sense that perhaps we, like Collins and dumas o’neal, can too reach for and bend the horizon into something livable, into something capable of satiating us in “every way possible,” without the threat of being severed at the wrists, blamed for the rupture and expected to find and reattach our own appendages.3

In regards to the internal current that animates “This Irrepressible Need to Fulfill Myself In Every Way Possible,” dumas o’neal writes: “Now, more than ever I feel the urgency to stop policing my own desire to engage in acts of retreat, leisure, and dreaming that are actualized outside of the social and political obligations that are often imposed on my being.” Perhaps then fulfillment ultimately also lies in our capacity to refuse the tendrils of guilt that snake their way into, devalue and rebuke our desires to simply, be.

Let us take a moment to return to and more fully consider the sentiment that undergirds this exhibition. Kathleen Collins writes: “October 12 — It is all about an urge, a powerful and overwhelming urge, to fulfill myself, to fulfill this life that is inside me, to fulfill it in every way leaving nothing untapped. That is what it is all about: the excess, the anxiety, the restlessness, the pain, carrying around in me this irrepressible need to fulfill myself in every way possible.”

Here, Collins ardently invokes totality. Fulfillment, for her, comes not in the form of perpetual happiness or joy. Rather, satiation arrives by way of “leaving nothing untapped,” which implies a willingness to surrender to unsavory (yet inevitable) aspects of a life fully lived: “anxiety, restlessness, pain.” In other words, “fulfillment,” for Collins, is not a terminal point. Instead, it resides in one’s ability to move through unavoidable periods of perturbation and undulate back towards a degree of fullness. Relatedly, dumas o’neal thinks of fulfillment as a “perpetual pursuit,” one that changes shape across seasons, as is the case in the landscapes she depicts throughout the exhibition.

It bears noting that while “anxiety, restlessness, [and] pain” are surely unavoidable elements of becoming, the magnitude and frequency with which we encounter them are symptoms of our entanglement with the tentacular grasp of capitalism. Within the hold of its stifling claws, we are manipulated into miring our sense of fulfillment in a debilitating pressure to achieve and expand at break-neck speed. Naturally, this leaves minimal space for rest, discourages us from engaging in the crucial work of dreaming, and paints one’s desire for slowness as frivolous, indulgent or, at worst, absolutely impossible to meet amidst the demands of everyday life. And yet, dumas o’neal’s work, whose very making is predicated upon the refusal of capitalist ideology (again, “this world is not enough”) in service of modes of thinking that ardently align with her needs, builds conditions for the birth of a different reality altogether.

After marvelling at entry #8 (if I dream it, I can have it), I ventured back into the main gallery space to spend time with the suite of seven photographs. After a cursory glance, I noticed that, like the film, six of them pictured horizons in various locations and times of day, recalling, again, the notion of the horizon as a metaphor for an “elsewhere” that loves us; and more specifically, an “elsewhere” we can visualize but not necessarily grasp yet (as was the case in entry #8 (if I dream it, I can have it), with the artist’s hand stretching into the space beyond).

Each of the photographs assumed collage-like form in that the colored images were all overlaid with smaller black-and-white images, which obstructed visual access to the horizon underneath. Chromatically speaking, the serenity and tranquility suggested by the delicate colors of the base photos was complicated by the wistful presence of their black-and-white counterparts, in turn adding to the generative tension catalyzed by the decision to place one photograph atop another. This use of layering, specifically over the horizon, brought to mind the political strategy of opacity or, in other words, the practice of intentionally restricting access to one’s interiority and the value such a strategy holds for Black women, in particular. We reach for the horizon, yes, for “elsewhere,” yes, and yet dumas o’neal’s work points to the necessity of refusing to disclose the particular directions and shapes our reaches assume.

Across all eight works in “This Irrepressible Need to Fulfill Myself In Every Way Possible,” dumas o’neal illuminates the fact that fulfillment often happens in the dark. That is, the asking and the answering of the question “what do I need to live a full life?” occurs the moment we grant ourselves permission to be illegible to the very systems that haunt our capacity to retreat into our inalienable totality.

Footnotes

1. As Octavia Butler reminds us in her magnum opus, Parable of the Sower: “There is no end to what a living world will demand of you.”

2. Remember and create because, as Audre Lorde reminds us in her essay “Poetry Is Not A Luxury”: “There are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt.” In other words, the blueprints exist. Our job is to slow down enough to listen for, recall and embody them.

3. Collins passes to dumas o’neal passes to myself: A conveyor belt or carrying of possibility. You understand. Find me reaching for the horizon. Find many more of us doing the same. Find us finding one another. Find us joining arms. Find us constructing something long enough ourselves. Something to grasp instead of only reaching.